In the Night I Dream: A Dreamlike Odyssey

A recipient of the DCP Award for Base Creators, Isioma Idehen explores the duality of belonging to more than one place, and the road to spirituality.

Every so often, a film arrives already humming with its own internal language— a story that feels less written and more remembered. In the Night I Dream is one of those works. Created by British-Nigerian multi-layered artist and director Isioma Idehen, this story was born from dualities it refuses to separate: between England and Nigeria, dreamworld and waking life, fear and faith.

What first pulled Isioma into Àdá’s journey wasn't a plot or an image. It was a return.

"Àdá’s journey began with me," Isioma shared. "I've always been a dreamer, quite literally. Since childhood, dreams felt less like sleep and more like visits... vivid, textured, sometimes poetic, sometimes unsettling."

Then the dreams stopped. For years, there was silence. When they returned, they did so with intention.

"They came with a weight, as if they weren't just memories of the night, but messages. Some echoed real life. Some predicted it... They felt alive. Present. Intentional."

For Isioma, the film wasn't just something she created, but something that insisted on being translated.

"It felt less like creating a film and more like translating something I had been living, sensing, and running from."

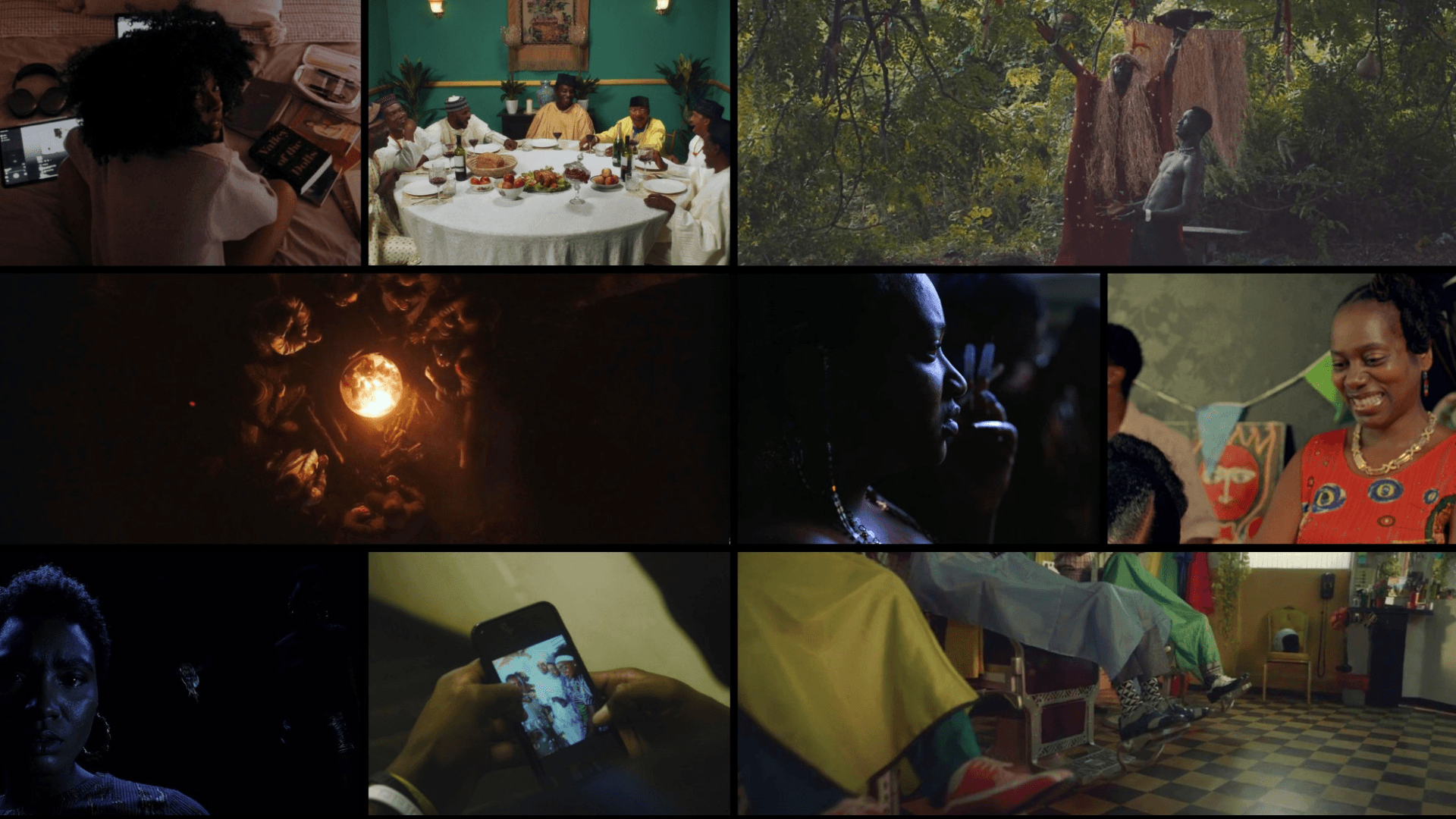

Two Timelines, One Becoming

The film moves between two geographies (England and Nigeria), but in conversation with Isioma, it becomes clear these aren't just settings. They're emotional and spiritual coordinates.

"It felt instinctive to build the film across dual timelines, because that's how I live," she explained. "I'm British-Nigerian, and my identity has always existed in motion, between two homes, two histories, two spiritual languages."

England carries the weight of structure and ritual. Nigeria holds spiritual clarity and ancestral return. Raised in England, Isioma grew up in Catholic schools and structures that shaped her moral language, but not necessarily her spiritual one.

Everything shifted when she visited Nigeria as an adult.

"That trip felt less like a visit and more like a calling. I began to understand that my dreams weren't random, they were ancestral... They existed in my bloodline long before I existed."

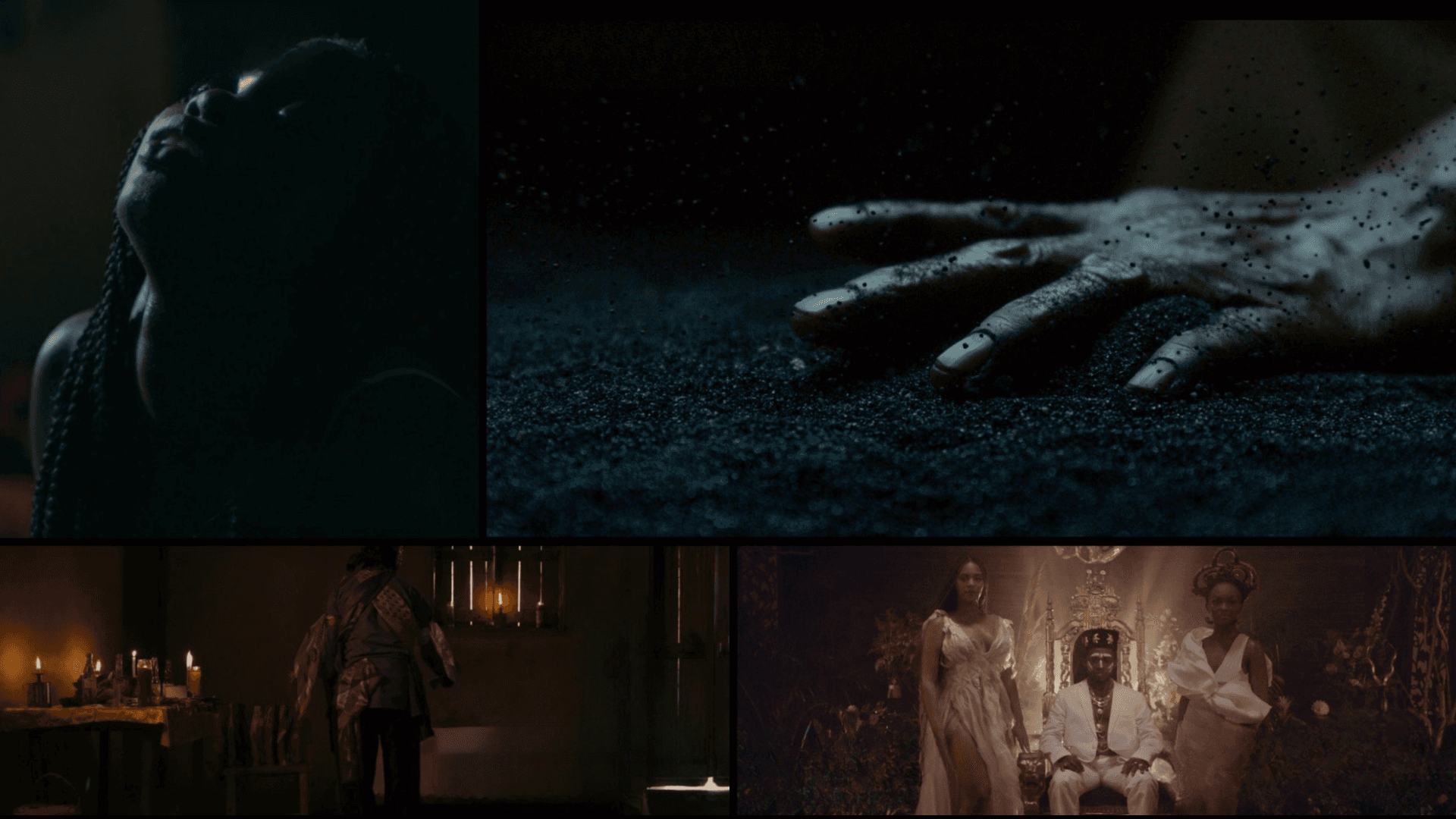

A Cinematic Language Built from Sound, Silence, and Spirit

At its core, In the Night I Dream is a sensory experience— a film that speaks through breath, pulse, and the echoes of ancestral presence.

That was intentional. The film has a lot happening, Isioma told us, and when there's a lot happening, there's at least one thing we need less of. For her, that was dialogue. She cut it out almost entirely.

Music carries the emotional spine of the story— the call, the memory, the haunting. This choice is deeply rooted in culture as well as personal identity. Music has always been a powerful expressive force within Nigerian and Black British communities, and Isioma honors that tradition with intention.

Sound becomes lineage. Rhythm becomes inheritance. The score becomes the bridge between waking life and the spiritual real.

Fashion as Cultural Language

One of the film's most striking, layered elements is its use of fashion— not as aesthetic decoration, but as a narrative device.

In the waking world, Àdá’s wardrobe is rooted in British culture: a blend of contemporary UK street style, diaspora expression, and the subtle codes of navigating European spaces while carrying an inherited inner world.

But in the dreamworld, the palette changes. Here, the wardrobe draws from rich Nigerian fashion: ceremonial fabrics, traditional patterns, bold color stories, and silhouettes that feel ancestral. The clothes in the dream life don't just dress Àdá— they recognize her, speaking to the lineage she is now returning to.

The wardrobe becomes a bridge between her worlds, a cultural compass that embodies an important theme in the film: you belong to more than one place, more than one language, more than one history.

Isioma's narrative choices, from music as dialogue and fashion as a symbol of return, highlight something essential about her: she's a multi-layered artist pulling from different mediums that shape her own story mirrored in Àdá's journey.

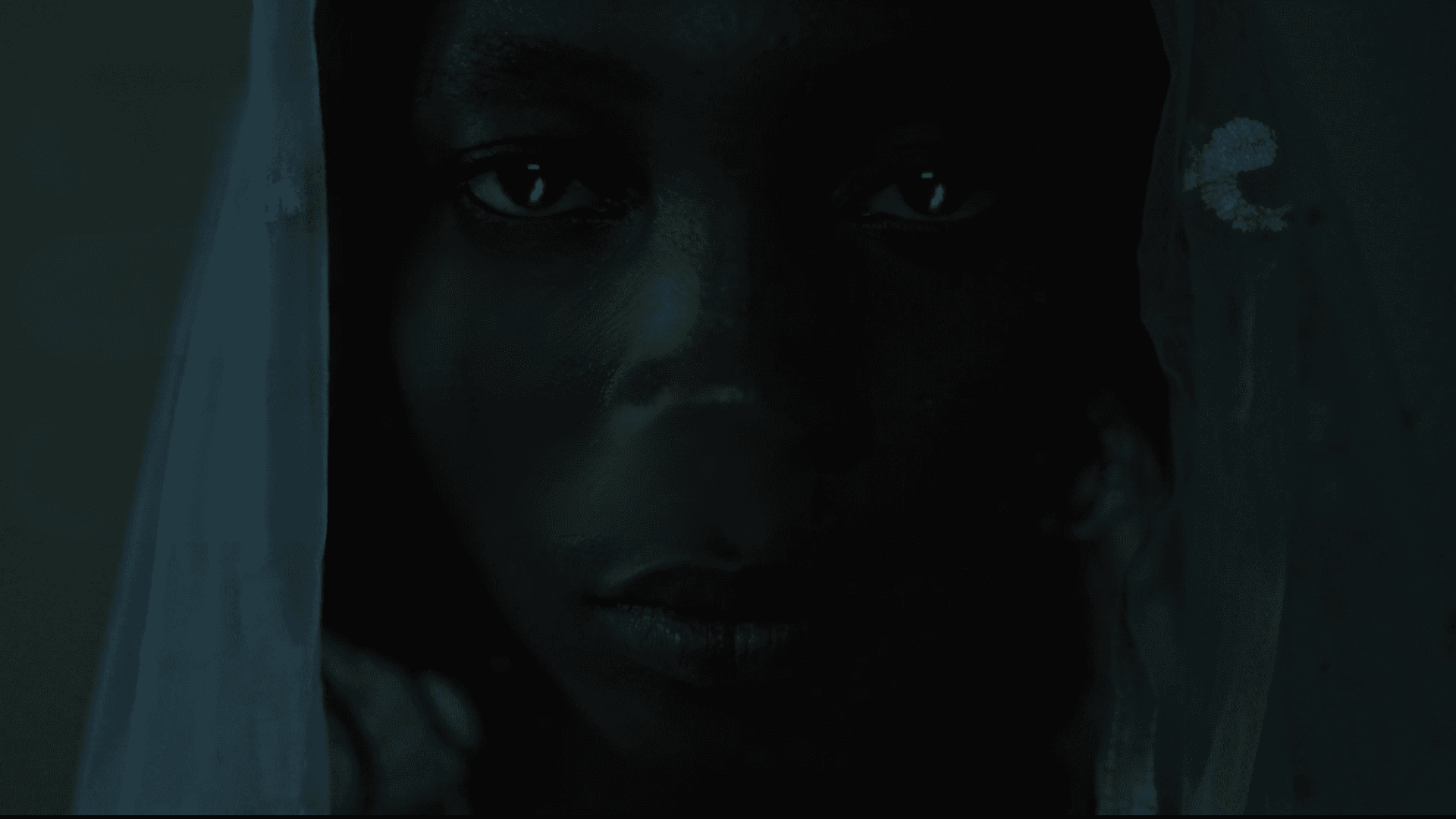

Horror in the Quiet Places

The film's horror-adjacent tone comes not from shock, but from uncertainty.

"What truly unsettles me is when reality feels unrealiable," Isioma said. "To me, horror isn't loud, it's subtle. It's the thing that lingers."

Her childhood memory— hearing her name called when no one had spoken— became the heartbeat of the film's atmosphere.

"That feeling, the questioning of what's real, what's imagined, and what might be spiritual... that's what guided me in the film's visual world."

So the horror becomes a flicker of a figure, a whisper that sounds almost familiar, a shadow that feels sentient, a silence that feels intentional.

"The atmosphere isn't designed to scare the audience, it's designed to make them feel what Àdá feels: pulled, questioned, called."

Onchain as Narrative Reclamation

"Narrative reclamation is at the heart of this film," Isioma explained. "For so long, stories about African spirituality have been told inaccurately... shaped through fear rather than truth."

Onchain spaces allow artists to bypass old gatekeepers, the ones who may not understand the nuance of diaspora experiences, and bring stories directly to the communities that hold them.

"Our communities are scattered all over the world, but onchain platforms allow us to gather in a way that is borderless and intentional."

Ownership is protected, authorship is honored, and value flows back to the creator. This is what drew Isioma to us here at DCP (and we couldn't be happier).

"I don't want to convert anyone through this film. I simply want us, as diasporans, to have access to our truths and to see beyond fear."

Full podcast interview to be published here.